Introduction

Socialist Industrial Unionism, developed by the American Marxist Daniel De Leon in the early 20th century, is a unique approach that organizes workers into a vertically integrated, multi-tiered system of industrial union councils, culminating in a supreme all-industrial union congress. This structure aims to establish direct control by workers over industrial production. This socialist framework seeks to transform the government's role to merely overseeing production, thereby enabling regional political autonomy.

It stands as one of the earliest concepts of a civilizational state, prioritizing the management of society's industrial inheritance over traditional national boundaries. According to De Leon, Industrial Unions aim to eliminate conventional political governance, focusing instead on societal management through worker control.

“Like the flimsy cardhouses that children raise, the present political governments of counties, of States, aye, of the city on the Potomac herself, will tumble down, their places taken by the central and the subordinate administrative organs of the nation’s industrial forces. Obviously, not the ‘structure’ of the POLITICAL movement, but the structure of the ECONOMIC movement is fit for the task, to ‘take and hold’ the industrial administration of the country’s productive activity-the only thing worth ‘taking and holding.’”

— Daniel De Leon, Socialist Reconstruction of Society

De Leon posits that for the economic strategy of Industrial Unionism to succeed, the groundwork of a robust union structure must be laid out in advance, ready to take over the state's functions once the party gains control. This entails the dual power of workers' unions being equipped to build a new governance framework, effectively replacing the traditional state apparatus. However, he acknowledges the continuing necessity for some level of political governance, especially in areas like law, social policy, and land management. This leads to a transformation rather than a complete abolition of political governance, with the emergence of semi-autonomous regional administrative zones. As a solution, the article suggests establishing regional land syndicates, a concept further detailed later in the discussion.

Socialist Industrial Unionism In The 21st Century

Today's landscape has dramatically evolved from the era of De Leon, with significant shifts that diverge from the expectations set by Marx. The post-Bretton Woods era did not see the anticipated subjugation of commerce to industrial capitalism. Instead, the FIRE sectors (Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate) have ascended to prominence in Western economies, underscored by the overarching influence of financialization over both commerce and industry. This shift underscores the critical role of establishing a national labor bank as a cornerstone for adapting socialist Industrial Unionism to the 21st century, a concept that will be further discussed. Moreover, we are witnessing the dawn of a fourth industrial revolution, marked by advancements in machine learning and automation, which promises to eliminate redundant managerial roles. Industrial Unionism aims to expedite this transition by dismantling the traditional bourgeois industrial and state administration in favor of large industrial syndicates governed by participatory democratic councils at various levels of industry. These councils could employ different methods of selection, including sortition, popular vote, or appointment, depending on the context. Workers would play a direct role in planning, aided by machine learning and automation, with some receiving additional compensation for their administrative contributions. This approach intends to marginalize the non-productive professional managerial class that profits solely from administrative rent.

Drawing from Georges Sorel's The Socialist Future of The Syndicates:

“The intellectuals have professional interests and not general class interests. These professional interests would be injured by the proletarian revolution. Lawyers would undoubtedly find no place in the future society and it is not likely that the number of diseases will increase. Progress in science and the better organization of assistance have already had the effect of diminishing the number of doctors utilized. In big industry many high-level employees could be eliminated if large stockholders did not need to place clients. A better division of labor would allow, as in England, the concentration of the work (now done badly by too many engineers) in a small group of very learned and very experienced technicians. As the character and intelligence of the workers improve, the majority of the overseers can be eliminated. The English experience abundantly proves it. Finally for office jobs, women compete actively with men; and these jobs will be reserved for them when socialism emancipates them. Thus, then, the socialization of the means of production would mean a huge ‘lock-out.” It is difficult to believe that the intellectuals are unaware of a truth as certain as this one!”

— Georges Sorel, The Socialist Future of The Syndicates

This widespread lockout targets superfluous management roles, suggesting these positions would transition into public and private sector jobs characterized by reduced labor hours and increased wages. This discussion leads to an intriguing idea termed The Techno-Industrial Diagonal by Edmund Berger. It presents a comparative analysis of the visions of Marx, Proudhon, and Sorel regarding the trajectory of industrial production in a post-socialist society, summarizing their distinct perspectives on how industrial development should unfold.

“Proudhon: political economy is value-neutral and akin to the natural sciences. Rigorous adherence to its discoveries will undermine capitalism and deliver socialism in the form of productive decentralization not unlike that of the pre/early capitalist era of craft production. Insofar as large-scale industrialization proves intractable, it will be managed by free associations of workers via a federative structure.

Marx: political economy is bourgeois mystification and the Proudhonists, while making pretenses of following a scientific methodology, consistently fail to exit the past’s metaphysical prison. Communism exists on the far end of a road paved by the dissolution of all past social forms through continually intensifying industrial progress, mechanization, and scientific rationalization. At the historical summit, seemingly endless mechanization collides with irreversible centralization and concentration of capital and productive forces.

Sorel: political economy is utopian and thus to be vigorously critiqued, but the Marxists also make appeals to a scientific methodology that they do not adhere to (particularly in regards to the development of techno-industrial systems). Intensification of class struggle in its syndicalist form—of which both Proudhon and Marx were the great prophets—will throw industrial progress into overdrive. It will not lead to the Marxian vision of centralization and concentration, however, but to the the rapid decentralization of productive forces—the proliferation of ‘prodigiously productive workshops’.”

— Edmund Berger, The Techno-Industrial Diagonal

It appears Sorel's perspective is gaining relevance, evidenced by the widespread adoption of a parcelled production model in consumer goods. Remarkably, in China, which stands as the current epicenter of world socialism, small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for 80% of non-government employment. This signifies a shift towards decentralized "prodigiously productive workshops," a development that aligns more with Proudhon's vision of society evolving into small artisanal workshops, though his complete forecast was off the mark. However, the relevance of contract work in trades within future socialism cannot be dismissed. Marx's prediction of the inevitable centralization of industrial production holds true, especially in sectors that deal with heat, pressure, and radioactivity, which remain highly centralized even in today's capitalist economies. Sorel's stance seems to merge the predictions of Marx and Proudhon, suggesting that while industries requiring large-scale machinery might centralize, those leveraging electric motors and robotics will trend towards decentralization, including land syndicate-owned and private firms. Additionally, the article highlights the overarching influence of finance, with financial planning gravitating towards centralized entities like Wall Street and the Federal Reserve. This context sets the stage for advocating a national labor bank, envisioned to serve both as a mutual credit bank and a cybernetic planning bureau.

Labor Money and the National Labor Bank

The envisioned national labor bank, operating as a state-owned mutual credit institution, will extend credit to both the public sector, including industrial workers' syndicates, and the private sector, aligning with a centrally planned economy while charging interest rates that merely cover administrative expenses and other related costs. As a cybernetic planning agency, it will analyze comprehensive supply chain data and utilize labor time calculations to guide production across various levels. In his critique of Proudhon's proposal for labor money in Misère de la philosophie, Friedrich Engels, in the preface to the 1885 edition, suggests that while Proudhon fails to conceive a libertarian social structure capable of implementing this, Rodbertus, with his admiration for Prussian organization, could envisage its realization through a highly centralized Prussian model.

To quote Engels:

“Rodbertus triumphantly shows us his splendid calculation, according to which the correct certificate has been handed out for every superfluous pound of sugar, for every unsold barrel of spirit, for every unusable trouser button, a calculation which "works out" exactly, and according to which "all claims will be satisfied and the liquidation correctly brought about". And anyone who does not believe this can apply to governmental chief revenue office accountant X in Pomerania who has checked the calculation and found it correct, and who, as one who has never yet been caught lacking with the accounts, is thoroughly trustworthy.”

— Friedrich Engels quoted in The Poverty of Philosophy by Karl Marx

The remarkable aspect of the discussed concept is that the generation and distribution of labor tokens could now be entirely automated, minimizing human intervention. Utilizing real-time supply chain and shop floor data, artificial intelligence could perform necessary labor time calculations and distribute labor credits to workers. This system would allow for adjustments based on performance, rewarding those who exceed the standard labor time with additional credits and reducing the allotment for those who fall short.

The labor bank would also provide various savings options, including retirement plans that offer annuities at predetermined dates and consumer savings accounts for future purchases of durable goods. To prevent hoarding and ensure alignment with the state's economic plan, labor credits would have an expiration date. In the private sector, labor credits could circulate freely, but exchanges for goods from the public sector would nullify the credits, helping to regulate the money supply and adhere to the state's objectives. Strategic and macroeconomic planning would be the purview of the all-industrial union congress (National Labor and State Assembly), decided through democratic processes. Microeconomic planning would occur from the shop floor upwards to the national level by industrial syndicate representatives. The AI based cybernetic planning system, managed by the national labor bank, would be supported financially by the marginal interest on loans provided to both the public and private sectors, covering administrative costs.

Land Syndicates

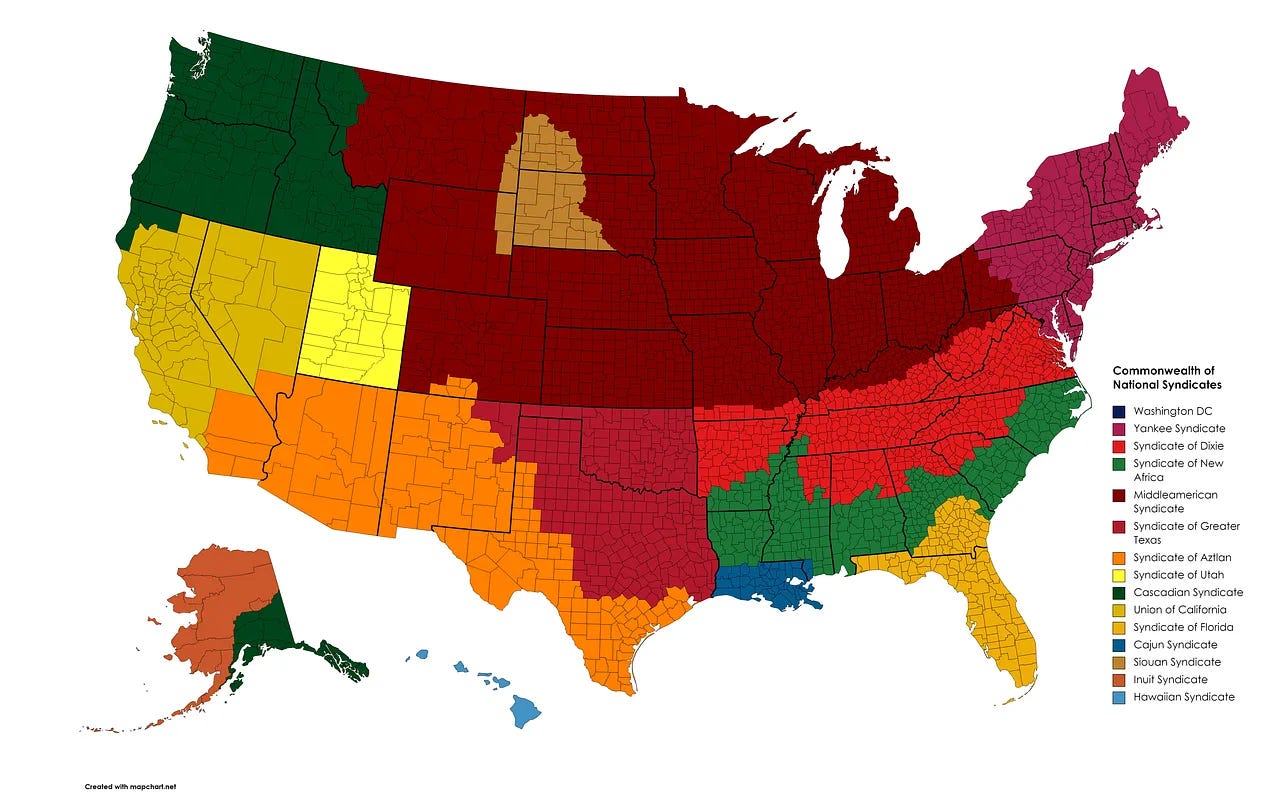

The topic of governance beyond industrial output has been previously touched upon in this article, proposing the establishment of "land syndicates" as a solution. These entities would operate as semi-autonomous regions tasked with legislating, implementing a land value tax to socialize land rents, and overseeing the development of essential infrastructure such as electric grids, plumbing, cellular networks, railroads, and more. Designed to align with specific regional characteristics, these syndicates would be directly accountable to their local populations. Moreover, they would manage social and welfare programs, leveraging their semi-autonomous status to accurately assess and meet their residents' needs. Zoran Zoltanous's article, Civilizational-States: Self-Determination of The Peoples? offers insight into how the distribution of these land syndicates might be organized:

Via Zoran Zoltanous